on feminism, motherhood, and working

It was Mother's day this past weekend and I miss my mama something fierce. Her motherhood is thoughtful and driven, creative and steadfast. She reminds my sister and I to spread our wings and fly, but to let our roots run deep, too. Now that my wings have brought me 3,000 miles away from her, I'm forcefully reminded of these roots. My heart aches every day at the thought of how far she is.

So today I think of the kind of mother she is. Witty, fierce, faithful (faith-full), practical, attentive, lighthearted, and sensitive. She is a woman of deep faith, a devoted educator, a caring keeper of her home, and a hardworking member of her community.

The celebration of my mother this weekend had me thinking about the kind of mother I aspire to become one day. It has always been my dream to live my way into motherhood (a most deeply held prayer), and I often find myself wondering about my someday-children; who they will be, and who I will be to them.

Motherhood and Choices

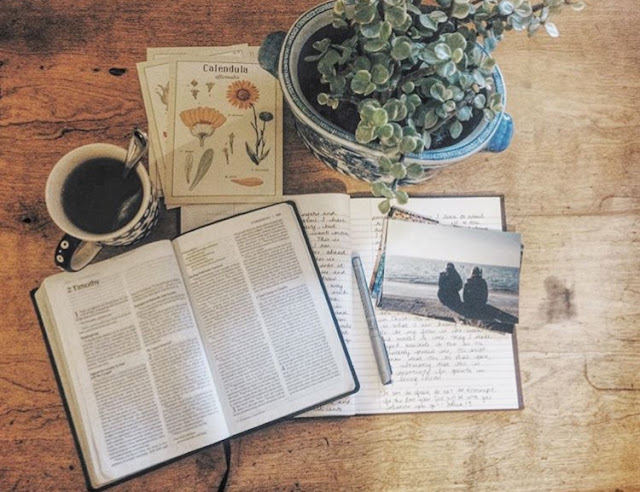

|

| My mother and I, in 1996 |

Motherhood and Choices

Although I dream of motherhood, I am also at an interesting season of life, with many competing ambitions and a budding career. Although I will only truly wrestle with these questions in years to come, I do think about what the nexus of motherhood and career will look like for me. My marital status still reads "single", and I am only at the very early stages of a career in communications and development. But I wonder nonetheless. I hope to pursue graduate studies in coming years, of making my way back to New York for further work with a development agency, of witnessing development programmes on the field. I am passionate about my field -about advocacy, the rights of the marginalized, and the importance of words and storytelling in development. These are things that matter to me on a guttural level, and where I have discerned a sense of calling over my life.

But I also believe I have the high calling of being a mother. I dream of being a mother -one who is present, who works with her hands, who exemplifies the path of faith to her children, whose words sing of adoration to her husband and children, who tends to a garden and her child's heart with deep attention, who delights in a houseful and gathers neighbors around the table, who cultivates a culture of peace and faith in her home.

And I periodically have this gnawing feeling that chasing after a successful career whilst simultaneously chasing after this type of relentless and committed motherhood is very difficult. I am not solely thinking about the "stay-at-home-mom" versus "working mom" fork in the road... I am even wrestling with whether being a mother inevitably requires sacrifices in one's career. And, if so, how should a woman hoping to one day become a mother approach and invest in career-building?

At this stage in my life, I speculate I will be a working mother in the future. This is the family culture I was raised in, and it is what makes the most sense to me right now. But, then again, who's to say what life will look like tomorrow? I can't really say.

But one thing I do know. I believe, fully, that if I have the privilege to one day be a mother, it will be my first ministry. If my employment made it impossible for me to mother well, I would have to loosen my grip on my career. This would be a no-brainer. Mothering, I assume, will be my greatest privilege and my most profound joy. At the end of the day, I think that the at-home mothers, working mothers, part-time working mothers and any-other-kind-of-mothers would agree that raising children is the most important of tasks. While I believe wholeheartedly that gainful employment outside the home is the best choice for many mothers, and that many women can successfully ascend the workforce while being tremendous mothers... I also believe that, whether I have a paid job or not, my priorities will be clear: keeping a home will always be more important to me than keeping afloat a dual-income household. In other words, whether I find myself to be an at-home mother or working mother, I do believe the most meaningful work I will ever do will be tending my family, nurturing young hearts, and creating a home for flourishing.

But it angers me to think that, more often than not, women have to choose between delving into a fulfilling career and proximity to their children. It frustrates me to think of how expensive and inaccessible childcare can be, especially in my new city context: the decision, generally speaking, ends up being a purely economic one instead of one based on true convictions. Too, many men have to make this choice (shout out to the stay-at-home dads out there!), but I do think the burdensome decision is largely shouldered by women. I recognize that much of this is because of the societal pressures that are piled onto women (ex: shaming the mothers who register their children for daycare, and who do not stay home full-time). But I don't think we can limit it to societal pressures and constructs. Perhaps it is narrow for me to say so, but I do believe women feel the tension of work and family in a further visceral, deeply rooted way. After all, we women are the forthbringers of humanity. We mother -in a million different ways. How could we not struggle with these questions most?

I don't believe there are many right or wrong answers when it comes to a woman's choice on whether/how she assumes, approaches or even outsources childcare. And while I suppose I could angrily glower at the fact that this world is not better designed for a person to be able to seamlessly accomplish both callings to her profession and motherhood, it would be naive to say a woman "shouldn't have to choose." We are all finite, and we all have to make prayerful decisions on how we want to spend the whole of our life.

Motherhood and Privilege

Motherhood and Privilege

And as I wrestle with all these questions (years before I even know if I will be a mother!), I am struck by the fact that I even have the possibility to think about such things. I am utterly privileged to be able to consider these options. It is not every woman's reality to be able to choose what her mothering and working life will look like.

I recently devoured Caitlin Flanagan's essay "How Serfdom Saved the Women's Movement," from a 2004 issue of The Atlantic. It is an absolutely captivating reflection on modern-day serfdom, working mothers, and the hypocrisy of privileged feminism (kind of like my rant above). To be clear, I employ the word "feminism" as the oh-so-radical belief that men and women are equal, and the consequent advocacy of women's rights to ensure this belief becomes reality. Privileged feminism, however, is the advocacy of women's rights with lacking understanding of one's social position and advantages. Specifically, it means defining the feminist struggle from a privileged perspective, and thus forgetting about the rights of women who are not white, wealthy, able-bodied, etc.

Flanagan, an at-home working mother who employs a nanny herself, here critiques the feminist movement's conflation of the hardships of poor working mothers with the insecurities (and guilt) of wealthier, working professional-class mothers whose struggles are a self-inflicted choice. In Flanagan's view, the latter group enters the workforce willfully -not as a result of the forces of global capitalism, as is the case of nannies. These professional-class mothers experience "mom guilt" (a reality I can fully empathize with, don't get me wrong!), but attempt to equate it to the oppression faced by the caregiver whose employment ultimately makes their white-collar careers possible. Flanagan argues that the "[...] the entire topic of nannies is the Achilles' heel of the feminist campaign to help professional-class mothers earn the right to (as they would say) mother and work without guilt."

And I have a million things to say. I heartily agreed with much of it -although it broke my heart and I practically shouted out in indignation when sifting through some of her points.

I do suggest you read the essay, but given its length, here is an extract that highlights the crux of her argument:

"The feminist movement, from its earliest days, has always proceeded from the assumption that all women—rich and poor—constitute a single class, and that all members of the class are, by virtue simply of being female, oppressed. In many regards this was once entirely true [...]. But this paradigm has led to a new assumption: that all working mothers—rich and poor—constitute a single class, that they are all similarly oppressed, and that they are united in a struggle against common difficulties. At its best this is vaguely well-intentioned but sloppy thinking. At its worst it is brutal and self-serving and shameful thinking. The professional-class working mother—grateful inheritor of Betty Friedan's realizations about domestic imprisonment and the happiness and autonomy offered by work—is oppressed by guilt about her decision to keep working, by a society that often questions her commitment to and even her love for her children, by the labor-intensive type of parenting currently in vogue, by children's stalwart habit of falling deeply and unwaveringly in love with the person who provides their physical care, and by her uneasy knowledge that at-home mothers are giving their children much more time and personal attention than she is giving hers. She feels more than oppressed—she feels outraged! she wants something done about this!—by a corporate culture that refuses to let a working mother postpone an important meeting if it happens to coincide with the fourth-grade Spring Sing.

On the other hand, the nonprofessional-class working mother—unhappy inheritor of changes in the American economy that have thrust her unenthusiastically into the labor market—is oppressed by very different forces. She is oppressed by the fact that her work is oftentimes physically exhausting, ill-paid, and devoid of benefits such as health insurance and paid sick leave. She is oppressed by the fact that it is impossible to put a small child in licensed day care if you make minimum wage, and she is oppressed by the harrowing child-care options that are available on an unlicensed, inexpensive basis. She is oppressed by the fact that she has no safety net: if she falls out of work and her child needs a visit to the doctor and antibiotics, she may not be able to afford those things and will have to treat her sick child with over-the-counter medications, which themselves are far from cheap. She is oppressed by the fact that—another feminist gain—single motherhood has been so championed in our culture, along with the sexual liberation of women and the notion that a woman doesn't really need a man. In this climate she is often left shouldering the immense burden of parenthood alone."

[...]

"It's easy enough to dismiss the dilemma of the professional-class working mother as the whining of the elite. But people are entitled to their lives, and within the context of privilege there are certainly hard choices, disappointments, sorrows. Upper-middle-class working mothers may never have calm hearts regarding their choices about work and motherhood, but there are certain things they can all do. They can acknowledge that many of the gains of professional-class working women have been leveraged on the backs of poor women. They can legitimize those women's work and compensate it fairly, which means—at the very least—paying Social Security taxes on it. They can demand that feminists abandon their current fixation on "work-life balance" and on "ending the mommy wars" and instead devote themselves entirely to the real and heartrending struggle of poor women and children in this country. And they can stop using the hardships of the poor as justification for their own choices. About this much, at least, there ought to be agreement."

...

I laud Flanagan's imploration to acknowledge privilege and to give credit where it's due. Without condemning the practice of nanny-hiring (after all, she has a nanny herself), Flanagan makes a compelling case against the woeful platitudes of professional-class mothers, who cry "Oppression!" whenever they face the tension of motherhood, nanny-hiring, and professional fulfillment. In her view, these women who hire nannies are in no way oppressed. Rather, they play an intrinsic role in a system oppressing other women -namely, the ones caring for their children. Nannies are in fact repeatedly denied the benefits required to transcend the very bottom of the multi-tiered American economic system.

The solution, Flanagan offers, is to lament the losses resulting from one's decisions while recognizing that these struggles, albeit legitimate, do not fall under the label of patriarchal oppression.

She encourages mothers like herself -who have had the luxury of choosing to either bow out of the workforce, quit their dream job, cut down hours or turn down profitable opportunities to be present with their children- to leverage their social position to advocate and further the rights of the mothers who are unable to consider such options.

And then she writes this:

"What few will admit—because it is painful, because it reveals the unpleasant truth that life presents a series of choices, each of which precludes a host of other attractive possibilities—is that when a mother works, something is lost."

Although blunt and clear, this was among the thorniest parts of the essay for me. But I've come to this conclusion: Flanagan is not saying that being a working mother means being a bad mother (again, she is a working mother herself), but rather that being a working mother inevitably means ceding time with one's children. This verity, albeit uncomfortable, is essential to come to grips with.

Likewise, she confers, this sacrifice can be grieved. While it does not constitute "oppression" but rather results from one's assumedly well-informed choices, it doesn't make the loss any easier to swallow.

Motherhood and Work

Motherhood and Work

I wonder about the "me" of the future who, I dare pray, will be blessed with the gift of children. Will she sense the pull to work outside the home? Will she choose to stay at home only for a time, or forever? Will she grieve when dropping them off at daycare day after day? Will she grieve the loss of a career of dreams to pursue another vocation of the greatest importance - rearing her children?

I wonder about the kind of mother I will be and, ultimately, give thanks for the model my mother espoused. For financial reasons, staying home was not an option for her when my sister and I were young. Perhaps, in another life, this is what she would have chosen. Alas, it wasn't to be.

I've only ever known my mother as a mother who worked outside the home -and worked hard, at that. She is a passionate educator and I could not be prouder of the ways she has impacted generations of students. She is creative, resourceful, and a true leader. And allow me to say this: her career was never a burden to us. She was not wronging her family by working, nor neglecting us. I find this conception of working mothers to be offensive -an overt generalization at best, and at worst a cruel misjudgment. Mothers work outside the home for a variety of reasons: some do so because they simply can and feel that they can meaningfully contribute to their communities outside their home, some have no choice at all (due to finances, for example), others do so for their mental health, or because they feel they can better mother when they've had time outside the home. Why arrogantly assume that working mothers take this decision lightly? Too often -especially in Christendom, I'm afraid, working mothers are characterized as aloof, distant, preoccupied, negligent, or dismissive moms with the wrong priorities. Needless to say, this is a far cry from my experience as the daughter of a working mom.

|

| My mother in her element as an educator |

In fact, I marvel at my mother's everpresent care and presence in our lives despite her full-time career. She sang words of love every morning we sauntered off to school, stood there waiting for us at the bus top at day's end from season to season, greeted us in her warm embrace on sunny and rainy days alike. She left an open Bible on the living room chair, beckoning us to walk the well-worn path of faith set before us. She prepared meals with care, and I remember the ease with which she swiftly chopped herbs from our garden or stirred a simmering pot of soup, and the way her fingers deftly kneaded fresh dough. On gloomy days, she added love notes to our lunchboxes. She volunteered on school trips and ballet committees and planned the best birthday parties on the block. She made holidays memorable through the work of her hands, whether it be her apple pies or Christmas cookies, dyed Easter eggs, or carved pumpkins. She helped us decipher our homework as children (and this, in her second language!). In my University years, she would bring me tea and pray for me as I studied for exams in the wee hours of the morning. She taught us to love our neighbors and invited ours into the home, even instituting a Christmas block party that all looked forward to. She loved our father with joyful, reckless abandon. She sang hymns and told stories and gave goodnight kisses. She answered our manifold questions, encourages us in our interests, delighted in our discoveries, echoed our prayers.

Sure, because my mother had to work outside the home, she was not able to cater to our every whim. We probably had to learn independence and responsibilities earlier than others. To some, this is too steep a sacrifice. In reality, though, I am grateful I did not grow up believing I was the center of my mother's universe. This isn't to say that mothers who stay home can't exemplify this balanced approach: I by no means view stay-at-home mothers as women who idolize their children and have no interests beyond their house. But I do think it important to dispel mischaracterizations and emphasize the following: my mother's work did not tarnish my childhood, and my years in daycare did not thwart my development. I am doing just fine. I never -ever- doubted that she counted her husband and children as her greatest earthly blessings. My parents dutifully ensured my sister and I were well taken care of and that we were grounded, too. I believe a mother who works or stays home can do this just as well.

I am not naive. Flanagan's essay made important points about the dark side of every mother's choices and level of privileges. I know that tending for us, homemaking, and cultivating such a strong sense of harmony and love in our household while also working full-time came at the cost of her energy and health at times (and my father's, too, to be clear!). It required grit, discipline and sacrifice. And while I am deeply grateful and proud to have witnessed my mama's leadership outside the home while also benefitting from her hard work in the home, I do recognize that I probably did not get the same amount of time with my mother as those whose mothers were able to stay home. On the other hand, I also see that there is an undeniable level of privilege involved in my mother's ability to hold a position that was so accomodating to family life. This is not to be taken for granted, either.

But as I contemplate what my future career and family might look like, I think this: if I am to be a working mother, I hope to be as she was to us -one who gave of herself freely to make a home, understood the importance of every sacrifice she made for her family (even when they broke her heart), recognized her privileges and fought for marginalized women (in word and in deed), consistently expressed and demonstrated her devotion to her children, while also cheerfully pursuing gainful employment to help support her family.

Motherhood and Freedom

|

| My mother, so loved by the children in our local church! |

Motherhood and Freedom

I love the words of the Hebrew Proverb on godly wives, generally recited by Jewish husbands as an ode to their wives on the weekly Sabbath, which read: "Her children rise up and call her blessed; her husband also, and he praises her" (31:28). The beauty of this passage as a whole is that it is not prescriptive, and grants freedom to mothers and wives on the way they live out their lives. When reading such words, I think, yes, this woman is my mama. And I hope it is me someday, too.

Similarly, my faith is an essential framework for my understanding of motherhood. As I consider these questions, I am reminded that God entrusts children to parents -despite all humans being flawed and broken- to do the holy work of shepherding them through this life, and leading them to His heart. But as mothers walk the sanctifying road of parenthood, He guides and equips them whilst granting them liberty about the particulars of childrearing. This is a comforting thought to me.

I know I've rambled on and on, but I wish to say this to close: let us be women who stand in confidence of our choices while applauding others in theirs, and contributing to systemic changes for those who don't have the ability to choose in the first place. We must all learn to name our goals, hopes, dreams, limitations, prayers, and divine calling -and make decisions in the knowledge of these facts. We must all consider what is best for our family's unique circumstances. The feminist framework bids women the opportunity to do so. But we must also recognize how our social position -our privilege, or lack thereof- informs such decisions. For those of us who do benefit of privilege, we must take Caitlin Flanagan's admonition seriously and relentlessly advocate for the interests of the mothers at the margins of society.

These conversations about feminism and motherhood are often filled with such ignorance, vitriol and shame-inducing commentaries. They foil our efforts at understanding and empathizing with every woman's distinct reality.

I am not a mother. But I pray I will be, someday. And when the day comes for me to be someone's mother, I hope to embrace motherhood as a testament of my love for that someone. And I have a hunch that most of us women hope this, too. When I take a moment to think of the mothers I know, I see that -no matter their context- they all desire to do right by their child. And it is important -staggeringly so- to consider how differently this hope materializes itself from person to person.

My mother's full-time work as an educator and counselor paradoxically enriched her motherhood -making her more attentive, pragmatic, sensitive, alert.

Conversely, my grandmother's heritage as a stay-at-home mother enriched her motherhood, too -making her more available, aware, deliberate, unhurried.

I love how different their stories are, yet how willful they both were in nurturing and bringing up their families. And perhaps, one day, this world will be one in which all women, whether intentionally or intuitively, can choose what their motherhood looks like... without fear of judgment or disapproval or shame.

My mother's full-time work as an educator and counselor paradoxically enriched her motherhood -making her more attentive, pragmatic, sensitive, alert.

Conversely, my grandmother's heritage as a stay-at-home mother enriched her motherhood, too -making her more available, aware, deliberate, unhurried.

I love how different their stories are, yet how willful they both were in nurturing and bringing up their families. And perhaps, one day, this world will be one in which all women, whether intentionally or intuitively, can choose what their motherhood looks like... without fear of judgment or disapproval or shame.

What will be right for me won't necessarily be right for you, but I think there's much beauty in the vastness and diversity of this call to the hard and sacred work of mothering.

So, today, I think of my someday-children and trust I will do everything in my power to best care for them and minister to their hearts. In the meantime, I am bottling up the things I am experiencing and learning and achieving and striving towards, reserving miles in my heart and mind to one day share and impart them all on the ones I will mother one day.

Today, I think of my mama and all the mamas -all so unique, all so different- and I whisper thank yous for the ineffably holy work they do.

|

| We three Debanné gals! |

Comments