advent and hope

In this neck of the woods, the stretch of weeks leading up to Christmas is full of wonder. Manhattan is clothed in mirth and merriment, with balsam fir lofted on bustling city avenues, church bells ever trilling, and light garlands glimmering with great ceremony.

And yet, this season of Advent has flooded me with a deep sense of weariness. Confusion has rolled over me like a crashing wave as I try to make sense of yuletide joy in light of brokenness.

I walk my neighborhood located in New York City’s poorest borough, marred by litter and backdropped by bellowing sirens. Here, I witness a different scene unfolding - and I wonder how to comprehend this season’s joy in a context devastated by unemployment, drug trafficking, and gang violence.

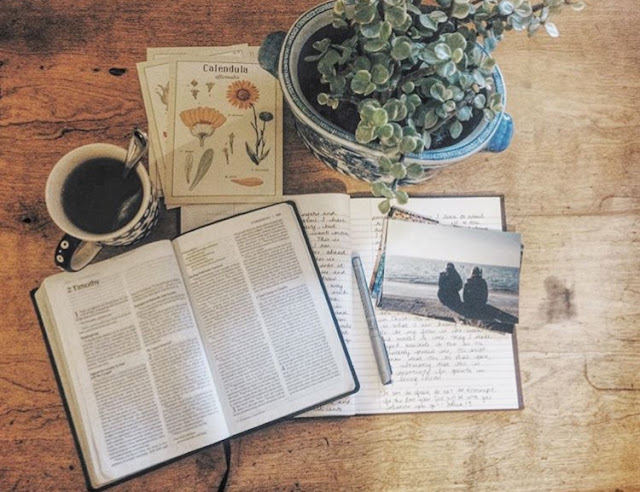

Week by week, I silently light a candle on the Advent wreath -but this familiar liturgy has brought to surface unfamiliar thoughts about suffering, poverty, strife, disease, oppression, violence and injustice.

I’ve grown to cherish the Bronx. Ever so slowly, I am learning to choose it as my own corner of belonging in this season of my life. I imagine that, years from now, if I visit this place again, I will see that I did much of my becoming here. As shared in this post, the Bronx has beckoned me to challenge and dismantle profuse ways of knowing and being, deeply ingrained and swiftly brought to light. It has gifted me a community that has surprised me and that I have come to cherish. It has been the place God brought me to the end of myself, kindly leading me to address messy patterns of sin, embrace a posture of incarnational ministry and surrender my white-knuckle grip on comfort and illusions of perfection.

Although I dare say good learning curves have come of this season in my new neighborhood, I still grapple with the contradictory nature of my life in New York: engaging in stimulating work in a polished Midtown office building, touring third-wave coffee shops and gaping at Christmas installations in the heart of the city- only to come home to broken glass in the lobby, the stench of weed and neighbor’s awaiting welfare cheques. Teenagers from the building spill into my living room as part of my roommate’s youth work. From my room, I hear the echo of their voices, and discern the grief of their speech. These children unwrap suffering in the form of prison visitations and social work meetings instead of gifts under a tree. Week after week, I plead with God: how do I reconcile “good tidings” when I coexist with other’s pain?

My rosy childhood, adolescence and early adulthood have never been overwrought by an abysmal sense of suffering or hardship. I recognize I have benefitted of much privilege, and of God's tender mercy. Hope has thus always been a complicated thing for me to grasp. For those who bask in nearly bottomless ease and enjoyment, what is the need for hope?

As I celebrated Advent in years past, my understanding of Advent hope was limited to a belief that the arrival of Jesus was the historic event that brought hope to humankind. The end. This was a convenient belief, as reliable and pleasant as a Christmas parcel tied up with a red bow.

Except I didn't really understand it, nor believe it.

When others disappointed, when my imperfections surfaced, when a grandparent went way of all flesh, when friends left, when conflict arose, when dreams died, when frustrations or struggles did not wane - this belief of hope perpetually extinguished itself, as swiftly as the four candle flames on the Advent wreath.

My own suffering was not systematic, nor prolonged, nor pervasive - but it was. I, like you, have lamented loss and deception and setbacks. I, like you, have ached for things to look and feel different. We all have had to confront and contend with the fateful realization, received as a call to arms, that it is not supposed to be this way.

Whether in my own life or in the conditions of systemic injustice and poverty experienced by my neighbors, the truth is this: every one of us live in a world dampened by sin and death. Coping with darkness is an unavoidable, intrinsic part of the human experience.

As I celebrated Advent in years past, my understanding of Advent hope was limited to a belief that the arrival of Jesus was the historic event that brought hope to humankind. The end. This was a convenient belief, as reliable and pleasant as a Christmas parcel tied up with a red bow.

Except I didn't really understand it, nor believe it.

When others disappointed, when my imperfections surfaced, when a grandparent went way of all flesh, when friends left, when conflict arose, when dreams died, when frustrations or struggles did not wane - this belief of hope perpetually extinguished itself, as swiftly as the four candle flames on the Advent wreath.

My own suffering was not systematic, nor prolonged, nor pervasive - but it was. I, like you, have lamented loss and deception and setbacks. I, like you, have ached for things to look and feel different. We all have had to confront and contend with the fateful realization, received as a call to arms, that it is not supposed to be this way.

Whether in my own life or in the conditions of systemic injustice and poverty experienced by my neighbors, the truth is this: every one of us live in a world dampened by sin and death. Coping with darkness is an unavoidable, intrinsic part of the human experience.

Week after week, as I perform the liturgy of Advent, I ask God to elucidate the notion of hope. I pray that the simple motions of lighting and blowing out a flame, and of speaking the familiar words "come, come, Emmanuel," would somehow tether my heart and mind to the promise that He is the light of the world.

As I watch the flickering blaze burn down to the wick, I ask God, again and again: how can I (how dare I) speak of hope in areas of this life and this world which appear to be utterly hopeless?

And, as I listen to the deep currents of my heart this Advent, I am reminded of this: Christ was born into the scarcity of a manger, surrounded by livestock, in a family of modest tradesmen and migrant refugees from Nazareth, considered a destitute and worthless place (John 1:46). The first to witness the arrival of the Messiah were shepherds, who ranked among the most ostracized members of society in the Ancient Near East. The looming shadow of the Roman Empire at both Christ’s birth and death indicate that He, like many of my neighbors, knew the reality of oppression at the hands of powerful political structures. He suffered through the brokenness of relationships, the deception of trusted ones, the aggressive tear of a friend's death. When His burden was too heavy to bear, His anguish and anxiety became corporeal, as He sweat drops of blood and cried agonizing tears. He faced humiliation, abandonment, and begged for the Father's nearness. He was pierced and mocked by those He came to deliver.

From His first to last breath, from the feeding-trough in the stable to the rugged cross, we see that the King of Kings knew and embodied suffering.

As I watch the flickering blaze burn down to the wick, I ask God, again and again: how can I (how dare I) speak of hope in areas of this life and this world which appear to be utterly hopeless?

And, as I listen to the deep currents of my heart this Advent, I am reminded of this: Christ was born into the scarcity of a manger, surrounded by livestock, in a family of modest tradesmen and migrant refugees from Nazareth, considered a destitute and worthless place (John 1:46). The first to witness the arrival of the Messiah were shepherds, who ranked among the most ostracized members of society in the Ancient Near East. The looming shadow of the Roman Empire at both Christ’s birth and death indicate that He, like many of my neighbors, knew the reality of oppression at the hands of powerful political structures. He suffered through the brokenness of relationships, the deception of trusted ones, the aggressive tear of a friend's death. When His burden was too heavy to bear, His anguish and anxiety became corporeal, as He sweat drops of blood and cried agonizing tears. He faced humiliation, abandonment, and begged for the Father's nearness. He was pierced and mocked by those He came to deliver.

From His first to last breath, from the feeding-trough in the stable to the rugged cross, we see that the King of Kings knew and embodied suffering.

Perhaps the invitation of Advent is to recognize and forcefully come face to face with the reality that our world groans for restoration and shalom. Perhaps hope takes on meaning when we grapple with the sting of death - of that which is not of Him. We, like the father and mother yearning for the arrival of the savior-child, can long for Him to come in the messy, dark and seemingly hopeless places of our earthside lives. While Christmas narratives oft manufacture senses of endless cheer, Advent is for the weary ones, the forgotten ones, the lonely ones, the grieving ones. It grants us space to lament that our world is still fractured, and grimly obscured by death.

In sitting in this truth, we can plead for God to come again, and to usher in a new creation: we herein find lasting hope that all the things of sin and death will one day be swallowed up in His victorious return, when He makes all things new- including this tangle of city blocks.

In sitting in this truth, we can plead for God to come again, and to usher in a new creation: we herein find lasting hope that all the things of sin and death will one day be swallowed up in His victorious return, when He makes all things new- including this tangle of city blocks.

Comments